Coffee! Climate, Waste, Cost, and Culture in a Cup.

A home-based comparison among French press, Moka pot and Capsule coffee

Introduction

This is not a scientific paper, nor was it written in a laboratory. It’s a simple, home-based experiment — something anyone can repeat in their own kitchen with a scale, a timer, and a bit of curiosity.

The goal is not laboratory precision, but understanding: using real numbers and common sense to see how our everyday coffee habits relate to energy use, waste generation, cost, and culture.

The guiding assumption behind all my blogs is simple: “Don’t trust me — do your own research.” For instance, the GHG data used here are based on the Italian energy mix; the situation may well be different in your country.

The figures presented come from direct observation and basic calculation, but the most important part is the invitation: try it yourself. Measure, compare, and taste. Coffee is one of the easiest ways to connect pleasure, science, and awareness — all within a single cup.

Pre-coffee summary (for lazy people)

If you don’t feel like reading the full story before your first espresso, here’s the essence:

- Scope: The article is only about consumer and waste generation stage of 3 coffee brewing methods.

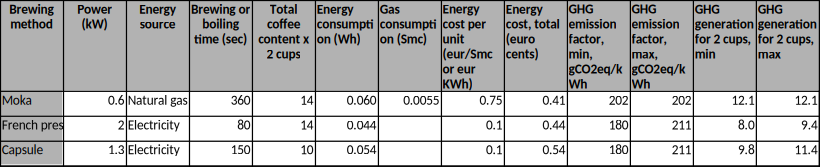

- Energy and CO₂. The French press is the cleanest (~8–9 g CO₂ for two cups), the capsule machine slightly higher (~10–11 g), and the moka on gas the most impactful (~12 g).

- Waste. The French press and moka leave behind only organic material that can go straight to compost. Capsules generate aluminum-plastic waste that is technically recyclable but rarely recycled.

- Cost. Beans and ground coffee are cheap; capsules are two to three times more expensive; “famous actor” capsules cost four to five times more.

- Pleasure. That’s subjective, of course. For me, the slower methods (moka or French press) win: I get aroma, ritual, and freedom to choose my preferred coffee or blends. The capsule is faster, but also flatter — coffee as a service

Energy consumption and GHG generation

Country Energy profile

The GHG impact may vary depending on your place. For electricity, I adopted the Italian CO₂ emission factors from ISPRA and Eurostat (“Greenhouse gas emission intensity of electricity generation in Europe,” 2025; ISPRA, n.d.), which give a range between 180 g CO₂ and 211 g CO₂e per kWh. These values reflect the current Italian energy mix, increasingly dominated by renewables but still partly reliant on gas.

Calorific value of natural gas.

For natural gas, SNAM reports a higher heating value (HHV) of about 10.57 kWh/m³ (“SNAM Annual Report 2020 – Operating review,” n.d.), while Casola (ENTSOG, 2022) (Casola Lopez, A, and Lanzillotti, S., 2022) gives a gross calorific value (GCV) of 39.96 MJ/Sm³, equivalent to 11.1 kWh/Sm³. These values describe the useful energy contained in one cubic metre of methane under standard conditions.

Experimental Setting

Calling it an “experimental setup” is probably too ambitious — but it serves the purpose. I simply ran my own tests at home, and I encourage readers to replicate the measurements and find their own data.

Three typical domestic coffee preparations were tested under comparable household conditions:

- Nespresso Machine – Two espresso cups: ≈ 90 seconds pre-heating plus 60 seconds brewing, using two capsules with about 5 g of coffee each. Power rating: 1.3 kW

- French Press – Two cups: 280 g of water heated to boiling, using about 14 g of ground coffee. Heating time: 80 seconds (electric kettle, 2 kW).

- Moka Pot – Two small cups: 105 g of water, about 14 g of coffee. Heating time: ≈ 6 minutes on a small gas burner at minimum flame (estimated thermal input ≈ 0.6 kW).

General formulas

For electric devices (kettles, Nespresso):

- 1. it is assumed that the electricity consumption may be calculated by multiplying the power rating by the usage time: El (kWh) = P (kW)×t (h)

- 2. to calculate the GHG emission associated to the electricity consumption, an emission factor based on the Italian energy mix is assumed: GHG_el (g CO₂e) =El (kWh) × EF_el(g CO₂e/kWh)

For gas hobs (moka), two equivalent routes:

- Energy route

- E_gas=P (kW)×t (h)

- CO₂_gas(g)=E_gas×200(g/kWh)

- Volume route

- V(m3)=CV(kWh/m3)E_gas;CO₂_gas=V×(200×CV)(g/m3)

Inputs used here (two cups baseline)

- French press: 2.0 kW kettle; 80 s to heat 150 g water.

- Nespresso: 1.3 kW; 90 s pre-heat + 60 s brew (150 s total).

- Moka: small burner at minimum ≈ 0.6 kW; 6 min to complete extraction.

Results (heating step only)

Based on these data, the French press results as the least impactful in terms of GHG emissions, while the moka heated on a gas burner generates the highest.

Waste Generation: What Remains After the Coffee

Once the last sip is gone, every brewing method leaves behind a trace — the physical evidence of our caffeine habit. Measuring these post-consumer residues doesn’t require laboratory precision: a kitchen scale, a curious mind, and a clean conscience are enough.

1. Organic waste

Each coffee method leaves a characteristic mass of spent grounds — the wet mixture of exhausted coffee and retained water.

- Moka.

A two-cup Bialetti moka uses about 14 g of ground coffee. After extraction, the puck weighs around 30 g, as the grounds retain part of the water that didn’t evaporate during brewing. This residue, entirely organic, can be disposed of with the compostable fraction or home-composted. - French press.

Using the same coffee dose (≈14 g), the French press produces slightly wetter residues — about 45 g of spent grounds — since immersion brewing leaves more water trapped between coarser particles. This too is pure organic waste and fully recyclable in the compost stream. - Nespresso-type capsules.

Each capsule contains roughly 5 g of coffee and yields about 10–12 g of wet grounds for two cups combined. The coffee residue is organic, but it’s sealed inside a small aluminum capsule that must be mechanically separated before either component can be recycled — an operation most consumers cannot do at home.

2. Packaging

Beyond the grounds themselves, the coffee’s journey adds another layer of material waste.

- Bulk or 1 kg bags generate about 15 g of plastic per kilogram of coffee.

- Smaller 250 g vacuum packs double that, around 30 g/kg.

For household doses (10–15 g per brew), this translates to 0.2–0.4 g of plastic waste per preparation — negligible in weight but not in persistence.

3. Capsules: the difficult case

Capsules change the scale completely. Each aluminum pod weighs 0.8–1 g, sometimes more. Two cups therefore produce about 2 g of aluminum waste, equivalent to ten times the packaging waste of traditional coffee.

Although aluminum is infinitely recyclable, capsules are not collected through standard municipal systems. Their mixed composition — metal plus organic residue, often with a polymer coating — makes ordinary recycling impossible. Specialized take-back programs exist, but participation rates are low, so most capsules end up as residual waste, either incinerated or landfilled. The actual amount of coffee capsule which is actually recycled is low, probably less than the 30% declared by Nespresso. (Elham Shirin, 2022; Ferguson and O’Neill, 2016; Marinello et al., 2021; “Recyclable Coffee Pods,” 2021)

Chemicals

Although the topic often surfaces as a concern (KOUMOUTSAKOS, n.d.), a review of available literature on chemical release from different brewing methods finds no consistent evidence of harmful levels of aluminum or other toxic compounds. For example, studies of aluminum migration from aluminum moka pots show that maximum migration corresponds to only around 4% of the tolerable weekly intake (TWI) for a typical consumer (Stahl et al., 2017)

Other work comparing brewing methods (moka, capsule, French press, filter) finds differences in the extraction of bioactive compounds (such as diterpenes, caffeine, chlorogenic acids) and in aluminum levels, but all measured concentrations remain well below health-based limits (“Coffee capsules,” 2025).

Specific observations include:

- Aluminum-made moka pots tend to show higher aluminum leaching compared to stainless-steel alternatives (Iscuissati et al., 2021)

- Capsule coffee machines may exhibit slightly elevated concentrations of endocrine-active or plastic-associated substances, but the studies show minimal or negligible exposure. (“Coffee capsules,” 2025)

In short: from a chemical-hazard angle, the differences between brewing methods are minor and, with current evidence, insignificant relative to health thresholds. As a practical guideline: the fewer materials and processing steps the coffee has to pass through before reaching your cup, the simpler and cleaner the path. In the case of the French press, the brew passes through a food-grade stainless-steel filter. High-quality moka pots are available in both aluminum and stainless-steel versions. Capsules are generally made of aluminum, sometimes coated with a thin plastic layer, and newer models may use compostable cardboard or biopolymer materials.

Additives: Flavoured capsules may contain a variety of flavouring agents, either natural or synthetic depending on the brand. Some capsule coffees also include food-approved thickeners, emulsifiers, or stabilizers to enhance texture or aroma retention. In general, however, simplicity is the foundation of both good taste and safer food. For coffee, this translates into the absence of chemical additives and the use of gentle extraction methods. Still, it’s worth remembering that coffee itself is a bioactive substance: excessive consumption can do far more harm than any trace additive.

Time, Cost, Taste, and the Price of the Brand

Since coffee is a pleasure and not a necessity, everyone is free to spend as much as they wish to enjoy it. Still, a few considerations are worth making.

Let’s start with taste. If you like having the freedom to experiment with blends, to explore coffees from different parts of the world, or to choose products with an ethical background, then capsule coffee is clearly not for you. And if preparing coffee is part of the pleasure — listening to a piece of your favourite music while the moka starts to sing, or enjoying the aroma released by the French press — these are pleasures that people who want to go straight from capsule to cup, without “wasting time” in between, simply don’t get.

Yes, preparing a moka may take up to ten minutes — but that time can be fully enjoyable if you use it chatting with a friend in the kitchen. The French press takes about five or six minutes. The capsule… well, a maximum of two minutes. Again, it’s your choice.

Now, let’s talk about cost — first the energy. Based on the calculations shown earlier, the energy cost of making coffee at home is roughly the same for the three methods, in the order of 0.2 to 0.3 euro cents per cup, the higher figure corresponding to capsule coffee. The main cost, of course, comes from the coffee itself. I’m not going to run a detailed market survey here — you can easily check these numbers yourself.

Go to a supermarket or browse online and compare the price per gram of the same coffee sold as ground coffee or in capsules. With few exceptions, ground coffee (for example, the usual 250 g packs) costs two to three times less than the equivalent quantity sold in capsules.

Whole beans are even cheaper: a one-kilogram bag of unground coffee costs about half to two-thirds of the price of pre-ground coffee.

And then we come to the price of the brand. A well-known capsule brand — I won’t name it, but everyone knows it, and everyone knows the famous actor promoting it — sells coffee for roughly twice the price of other good, but less advertised brands: around €0.50 per capsule, compared to €0.18–0.25 for equally good alternatives.

In practice, the annual cost for two persons drinking 2 cups per day, as of November 2025 will be:

- Good coffee beans (about €15/kg) → €0.09 per cup ~ €135/yr

- Good ground coffee → €0.14 per cup ~ €208/yr

- Quality capsule coffee → €0.18–0.25 per cup ~ €266 to €368/yr

- The “famous” capsule → €0.50 per cup ~ €733/yr

Personally, I’m not willing to pay for the brand. I don’t find it rational, fair, or even morally justifiable. And if that brand premium also comes with an environmental cost — unnecessary waste and avoidable resource consumption — then it becomes even worse. In that case, I would basically be financing environmental damage at about 1.4 eur a day, or more than 500 a year, assuming two coffees a day per two persons.

Everyone is free to do as they like, but it’s important to be aware of what one is doing. In my case, I’m perfectly happy enjoying my daily coffee — one French press and one moka —, while giving the difference as a donation to humanitarian organizations. Quite the opposite of funding waste generation.

References

- Casola Lopez, A, and Lanzillotti, S., 2022. Insights on the changes in the Italian natural gas supplies.

- Coffee capsules: implications in antioxidant activity, bioactive compounds, and aluminum content, 2025. . ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-020-03577-x

- Elham Shirin, 2022. Coffee capsules: Brewing up an (in)convenient storm of waste. Mongabay Environmental News. URL https://news.mongabay.com/2022/12/coffee-capsules-brewing-up-an-inconvenient-storm-of-waste/ (accessed 11.9.25).

- Ferguson, Z., O’Neill, M., 2016. Former Nespresso boss warns coffee pods are killing environment. ABC News.

- Greenhouse gas emission intensity of electricity generation in Europe [WWW Document], 2025. URL https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/greenhouse-gas-emission-intensity-of-1 (accessed 11.8.25).

- Iscuissati, I.P., Galazzi, R.M., Miró, M., Arruda, M.A.Z., 2021. Evaluation of the aluminum migration from metallic seals to coffee beverage after using a high-pressure coffee pod machine. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 104, 104131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2021.104131

- ISPRA, n.d. Indicatori di efficienza e decarbonizzazione in Italia e nei principali Paesi europei. Edizione 2025 [WWW Document]. ISPRA Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale. URL https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/pubblicazioni/rapporti/indicatori-di-efficienza-e-decarbonizzazione-in-italia-e-nei-principali-paesi-europei-edizione-2025 (accessed 11.8.25).

- KOUMOUTSAKOS, K.P., Georgios, n.d. Parliamentary question | High concentrations of furan in coffee capsules | E-004228/2011 | European Parliament [WWW Document]. URL https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-7-2011-004228_EN.html (accessed 11.9.25).

- Marinello, S., Balugani, E., Gamberini, R., 2021. Coffee capsule impacts and recovery techniques: A literature review. Packaging Technology and Science 34, 665–682. https://doi.org/10.1002/pts.2606

- Recyclable Coffee Pods: Sustainability Villains to… [WWW Document], 2021. . Euromonitor. URL https://www.euromonitor.com/article/recyclable-coffee-pods-sustainability-villains-to-sustainability-champions (accessed 11.9.25).

- SNAM Annual Report 2020 – Operating review [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://reports.snam.it/2020/annual-report/directors-report/business-segment-operating-performance/natural-gas-transportation/operating-review.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed 11.8.25).

- Stahl, T., Falk, S., Rohrbeck, A., Georgii, S., Herzog, C., Wiegand, A., Hotz, S., Boschek, B., Zorn, H., Brunn, H., 2017. Migration of aluminum from food contact materials to food—a health risk for consumers? Part II of III: migration of aluminum from drinking bottles and moka pots made of aluminum to beverages. Environ Sci Eur 29, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-017-0118-9

Written by Carlo Lupi (2025). Editorial support provided by AI (OpenAI GPT-5). Published under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. All human and AI contributions acknowledged.

Comments are closed